Key insights of today’s newsletter:

Last week it was reported that a fake Joe Biden robocall urged New Hampshire voters not to vote in the upcoming Democratic primary.

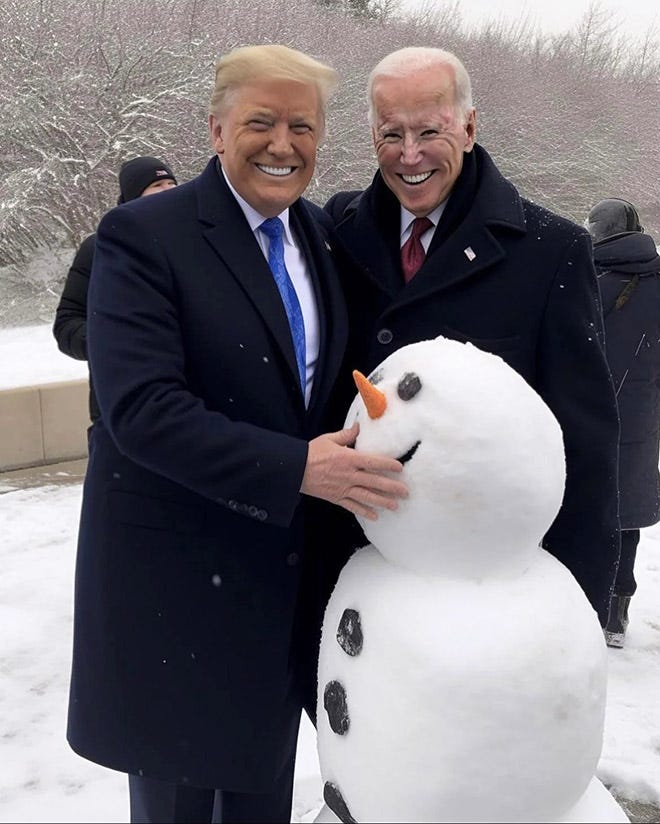

Increasingly convincing deepfakes and voice clones are stoking fears about the rise of AI-generated misinformation.

A second-order effect of deepfake technology is that it creates plausible deniability for politicians and public figures, by claiming real footage as AI-generated.

↓ Go deeper (5 min read)

What’s the difference between a drowning woman and democracy? The drowning woman can be saved.

Democracy is a conversation between people. A conversation built on trust. When that conversation breaks down, democratic institutions are weakened and may crumble, when enough pressure is applied.

Anno 2024, much of that conversation happens online. So far it has been a mixed bag. News travels faster than ever, yet, the same can be said for fake news. The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is much bigger than that is needed to produce it, and the cost is only going down.

While online misinformation clearly is a multifaceted problem, it looks like with the arrival of generative AI, the monster has just grown another head.

Fake Joe Biden call urges people not to vote

This month, we got a first glimpse of what’s coming, when it was reported that a fake Joe Biden robocall urged New Hampshire voters not to vote in the upcoming Democratic primary. It was a coordinated effort: somewhere between 5,000 to 25,000 calls.

Meanwhile, over in the UK, The Guardian reported that more than 100 deepfake video advertisements impersonating Rishi Sunak were paid to be promoted on Facebook in the last month alone.

The impact of such campaigns is subject to fierce debate. Generative AI has the potential to supercharge online misinformation, but some experts say those fears, while understandable, are largely overblown. They argue that any increase in the quantity or quality of misleading content would be largely invisible to most of the public, as research suggest that only a small minority of people gets exposed to it.

To me, the idea that misinformation will become more persuasive, but it won’t reach the right people, seems naive. This sounds more like a distribution problem than anything else; a problem that can be easily solve through better targeting. At a group or even individual level.

AI will provide bad actors with an aura of plausible deniability

But even if you were to believe that AI-generated misinformation won’t move the needle in upcoming elections, the fear for it may be enough on its own.

The worry alone could further erode trust, similar to how the weaponization of the term ‘fake news’ has become an effective rally-cry that has undermined the public trust in traditional media reporting (regardless of whether or not said reporting has in fact become less trustworthy).

Another knock-on effect is that it creates “liar’s dividend”. This term was coined by law professors Bobby Chesney and Danielle Citron in a 2018 paper: as people become more aware of how easy it is to fake audio and video, bad actors can weaponize that skepticism. It creates plausible deniability.

We’ve already seen this from Elon Musk and January 6th rioters, who raised questions in court about whether video evidence against them was AI-generated. And last week, The Washington Post ran the headline:

This came after Fox News aired an anti-Trump ad, featuring an authentic video of the former president struggling to pronounce the word “anonymous”. Trump claimed the people behind the ad had used AI to make him look bad.

The Post notes that around the world, AI is increasingly being used as a shield for politicians to fend off damaging allegations. While such claims may be easy to disprove in some cases, in other cases it might not.

Counterfeiting people

The final nail in the coffin of democracy could be counterfeit people, according to Daniel Dennett, a respected American philosopher and cognitive scientist.

In an essay he published for The Atlantic, he writes:

Today, for the first time in history, thanks to artificial intelligence, it is possible for anybody to make counterfeit people who can pass for real in many of the new digital environments we have created.

(…)

Before it’s too late (it may well be too late already) we must outlaw both the creation of counterfeit people and the “passing along” of counterfeit people. The penalties for either offense should be extremely severe, given that civilization itself is at risk.

Similar to counterfeiting money, counterfeiting people (and us not being able to tell the difference) could undermine public trust.

While I sympathise with Dennett’s plea, it is steeped in pathos. The problem he’s describing is also not that new. As long as I can remember, social media platforms have struggled with fake accounts used to organize misinformation at scale (Russian troll farms? Cambridge Analytica?).

A real people policy that requires people to verify their identity in order to create an account may be a first step towards a solution. Twitter/X’s blue checkmark system seems like a good step in that direction — it’s something I’d love to see more platforms push for more aggressively.

What it won’t do, is solve the problem of deepfakes and voice cloning. Political deepfakes are going to be all over the place and I see no way of stopping it, other than through increased efforts in content moderation. Also, it’s not just politicians that’ll have to fear for them. Anyone can fall subject to impersonation — public figure or not.

In the meantime, those seeking plausible deniability have been conveniently handed an escape hatch. Yikes!

Join the conversation 🗣

Leave comment with your thoughts. Or like this article if it resonated with you.

Get in touch 📥

Have a question? Shoot me an email at jurgen@cdisglobal.com.

What comes to mind is the New York Times having an AI lab.

If they literally feel they need to spend millions of dollars on that what do you suppose comes next for the Free press of the world?