Summary: Companies are building AI systems to replace white-collar workers. Despite that, employment in the US and Europe is up and global productivity is down. So, when will we see the impact of AI automation? And when it’s here, will it lead to mass unemployment?

↓ Go deeper (12 min)

In many ways it looks like AI is here to replace us. Last week, Microsoft announced the launch of autonomous agents as part of their Copilot offering, Apple developed a system that can control apps across all Apple device, and Anthropic released Computer Use for Claude in beta. In other words, your computer can now use your computer for you.

Meanwhile, startups are racing to develop AI assistants that can take on entire jobs. We have Devin’s “first AI software engineer”, Cosine’s “AI colleagues that are truly autonomous”, and Intercom’s Fin 2, the first AI agent that “delivers human-quality service”. And did you know there is a Netherlands-based start-up that presents their AI’s as employees with salaries?

Where does this obsession with replacement come from? And is mass unemployment the inevitable outcome of this process? To answer these questions, we’ll have to dive into the economics of AI.

Global productivity is down

According to OpenAI, ChatGPT has roughly 200 million active users, twice as many users than a year ago. Arguably, ChatGPT is already doing the work of many workers combined. Yet, global productivity is down and employment in the US and Europe is up.

It is very well possible that the real impact of AI automation is a few years away still. To compete, it will need to be as cheap or cheaper, and as reliable or more reliable than their human counterparts for companies to effectively replace workers with it. In some cases, AI could even be less reliable than humans, if it was much cheaper to use and deploy.

Let’s look at call centers as an example.

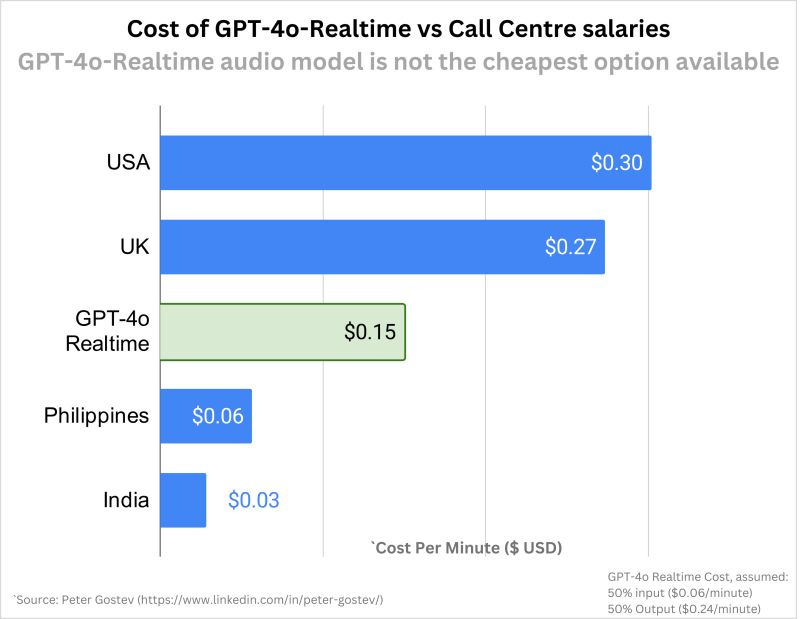

The cost per minute usage of GPT-4o’s Realtime API, which processes voice input and output in realtime, is cheaper than the cost per minute of a US-based human call center agent answering phone calls. (Of course, this doesn’t take into account the cost of building a system that would guarantee the quality of the output is on par with real human call center agents.)

Somewhere between 2.5 to 3 million people work as contact center employees in the US — to anyone working a job like that, this is a very scary graph.

Like I mentioned, another major trend is teaching computers how to use computers, as evidenced by releases from Anthropic, Apple, and whatever Google is cooking up behind-the-scenes.

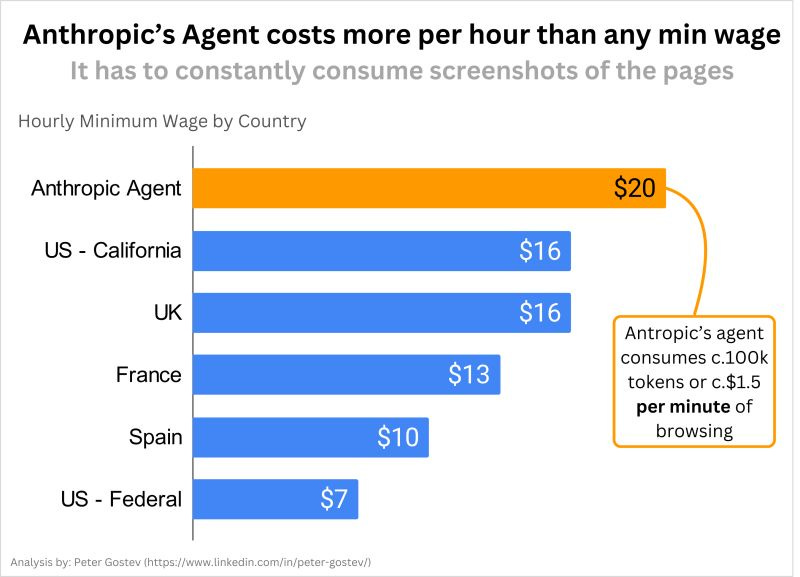

Currently, this tech is too expensive. Claude’s Computer Use costs about 20 dollar per hour of use, more than any minimum wage in the world. (To be fair: a whole lot of people get paid a whole lot more to sit behind a computer all day). Also, we should keep in mind that the costs drop significantly every 6-12 months and what may be costly today could be much cheaper in the future.

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on how you look at it), Claude’s Computer Use is also terribly unreliable. Here’s an excerpt from Anthropic’s own explorations:

“Even while recording these demos, we encountered some amusing moments. In one, Claude accidentally stopped a long-running screen recording, causing all footage to be lost. Later, Claude took a break from our coding demo and began to peruse photos of Yellowstone National Park.”

This is probably less amusing if it was used in a business context, losing or destroying real business progress.

Higher economic output

For both examples, the use of computers and fully automating the work of call center agents, reliability is the true bottleneck for viability and I expect it to remain so for a while.

Don’t get me wrong: if you’re a white-collar worker, AI is coming for your job. Economics 101 teaches us that when costs and reliability converge, replacement of workers will not only become feasible but also the more cost-efficient option. And in a global economy driven by market incentives, the markets decide. Jobs will disappear.

Factory workers, lamp lighters, switch board operators, aircraft listeners — a lot of jobs that once existed have perished.

Is this bad? Not really. A recent study by economist David Autor found that 60% of today’s workers are employed in occupations that didn’t exist in 1940. This implies that more than 85% of employment growth over the last 80 years can be explained by technology-driven creation of new positions.

What technology does, and arguably AI will do too, is increase the average economic output per individual. In other words, we can do more with less, which usually means one of two things:

Achieving the same or more with fewer people. This is a form of bottom-line savings, where increased productivity reduces the resources needed to achieve the same output.

Achieve more with the same amount of people. This is considered top-line growth, where you grow the business without reducing costs or increasing resources.

Asked about fears of AI’s impact on employment, Charles Lamanna, corporate vice-president at Microsoft, told the Guardian that agents help with the mundane, monotonous aspects of the job:

“I think it’s much more of an enabler and an empowerment tool than anything else. The personal computer didn’t show up on every desk to begin with but eventually it was on every desk because it brought so much capability and information to the fingertips of every employee.”

I think he’s right. I don’t think mass unemployment is inevitable. In fact, I expect the opposite to happen. If AI delivers on its promise, the individual productivity of people could skyrocket — it may triple or even quadruple, in some cases — which is exactly what we need if we want the global economy to continue to thrive and national GDPs to grow over the next few decades.

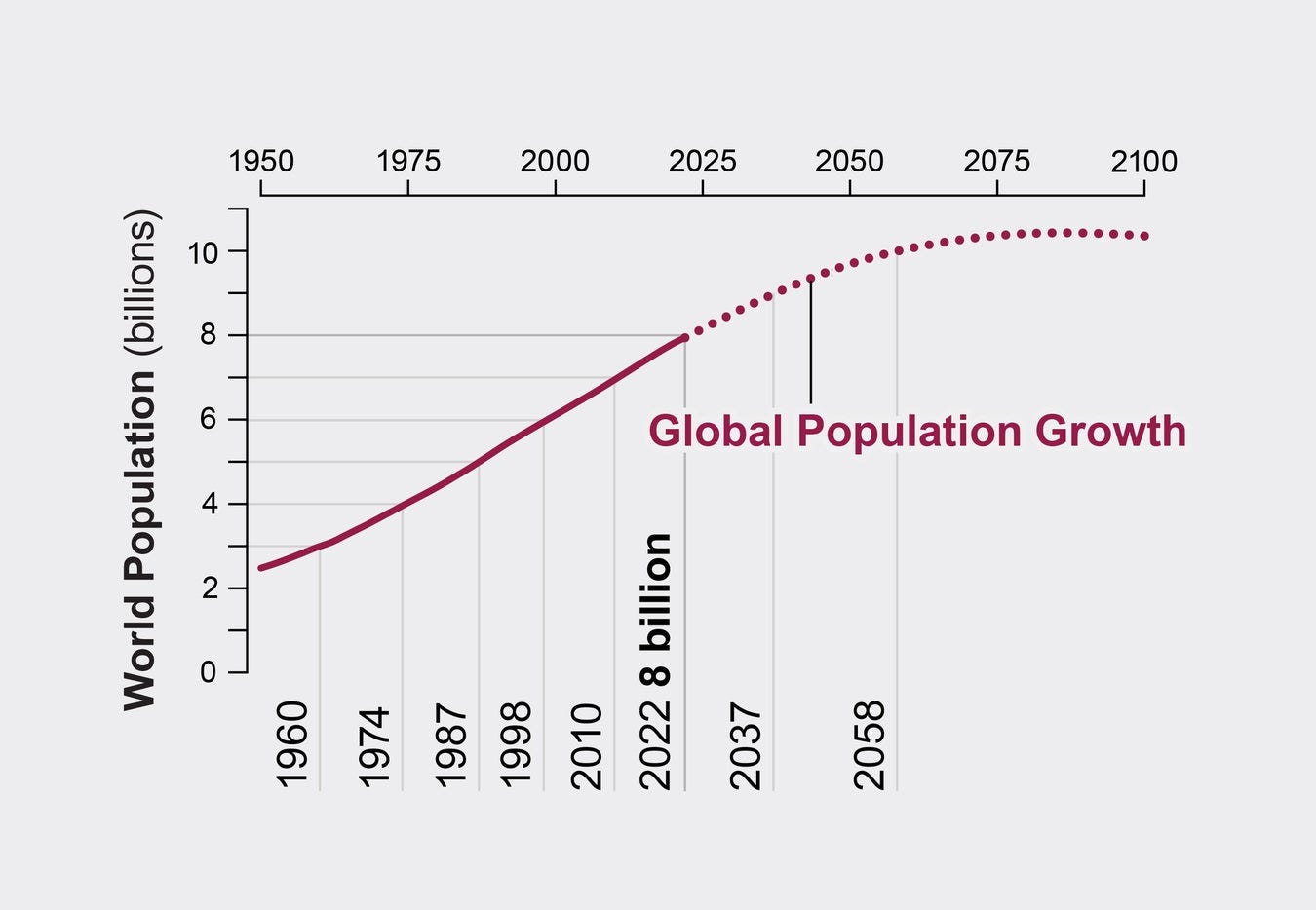

Why? Throughout history, Earth’s population has continued to grow. Our economies rely on this growth. However, current projections suggest that this long-term trend may be coming to an end. As societies get more prosperous, people get older and tend to have fewer children. As a result, younger generations have to carry the economic weight of an increasing aging population. Japan is the most famous example of this. But also Germany, with more than 20% of the population being 65 or older, is currently facing declining birth rates and an aging society, similar to other European nations.

It’s not a controversial statement to say that in the best-case scenario, the answer to global population decline is a future where individuals are supercharged by AI. Where old jobs perish, but new jobs are created that didn’t exist before technology brought them about. Who would’ve thought that teaching computers how to talk would even be a job? Now it is.

Kill them with kindness,

— Jurgen

Nothing wrong with your optimism, but so far there is scant evidence that genAI is amplifying human abilities. It was designed to replace them, its founders talk about replacing people, and the first target for replacement was creative work: something we actually enjoy and don't want to replace. Market forces and CEO greed is turning this into a race to the bottom, with no plan in place for how to deal with the fallout.

I am not an economist, so below are my 2 cents based on my observations, reading, and experience, and since it is a sample size of 1, I could be way off:

1. I do not look at jobs only based on the number of jobs created by a new technology. Will these newly created jobs pay as much or better than jobs that will disappear? What would be the quality of employment? Are these jobs going to motivate people to go to work, or is this one of the Bullshit jobs mentioned in this book (https://tinyurl.com/msckmhxd)? Note: I'm not 100% in agreement with this book, but I think it is mainly true.

2. Also, if the new jobs require little or no skill or very high skill, the former will be boring for skilled people, and the latter will create a situation in which there may not be enough people to do the jobs even after AI augmentation.

3. Also, doing more with fewer people or doing more with the same number of people is an excellent way to consider AI benefits if they ever become realized. However, in the short term, it may create higher unemployment since companies will hire fewer people or not look for replacements once someone leaves.

4. My other fear is that companies will stop hiring people with no or little experience if they get very high productivity from experienced people. There won’t be a lot of incentive to hire low—or no-experience people, creating a long-term situation where we will not have a pipeline of experienced people.

5. We may see a lot of pushback from people who think AI will threaten their jobs. I recently read in the Washington Post (https://tinyurl.com/4jk32red) that even doctors do not want to use AI in their work because they think it would be an excuse for insurance and hospital administrators to cut staff in the name of innovation and efficiency.

6. As someone said, “As soon as it works, no one calls it AI anymore, and it is software.” It will become part of the software and be introduced without people knowing it exists.

7. I agree that we will eventually need AI and robots to keep the world growing as the birth rate continues to drop and there are not enough working-age people. However, we are not there yet. Do we still need very high growth if we have fewer people, as older people, either way, consume much less?

8. How will we compensate people who will lose their jobs? Yes, universal basic pay is an option. However, most of us work not only for money but also because it gives us a purpose and a reason to wake up in the morning. A few people say you can travel and work on your hobbies, but I do not think it is for everyone or most people. You can do these things for so long after that you want to do something similar to a job as you want to feel valued and add value to your organization, community, and society.

9. Very few companies will say it will replace people's jobs as they do not want people to think their product is a threat, even though they know this is the case.

10. Drawing parallels between AI and past technological revolutions may be misleading. While previous innovations like the printing press, steam engine, or computers primarily automated physical tasks or streamlined existing workflows, AI represents something fundamentally different - it's the first technology designed to replicate and potentially surpass human cognitive abilities. Unlike past transitions where humans could shift to roles requiring higher thinking, AI targets these very cognitive tasks. While new jobs may emerge, as they did with previous innovations, we cannot rely on historical patterns when facing a technology that competes with human intelligence itself. As uncomfortable as this conclusion may be, we're in uncharted territory. I do not like to say that, but it may be different this time.

To summarize, we need to be ready for a worst-case scenario in which there would be a lot of unemployment, and many people may not find purpose without jobs. We should plan for it and hope we do not see it.

Thoughts?