Summary: Some people believe AI is giving rise to a new industrial revolution. If so, society as we know it will transform, some jobs will be lost and while this may sound counter-intuitive that may not be the worst thing in the world.

↓ Go deeper (15 min)

A question burning in the back of my mind for a while now is how AI is going to impact the job market. A cliché that gets thrown around a lot is that “AI will not replace you, but people using AI will”. An alternate version that Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang likes to use, is that AI is going to “automate 50% of the work for 100% of the people”. It’s catchy, but when you really think about it, it doesn’t quite make sense.

What’s clear is that when it comes to the topic, different people believe different things. Some believe AI is going to augment us. Others think full automation of all cognitive labor could come as early as 2027 and that the first group is in denial.

To figure out whether these predictions ring true, and to answer the question of whether more automation is good or bad, three global trends may shed more light.

Higher life expectancy

To say anything meaningful about the future, one should look to the past. So, let’s zoom out.

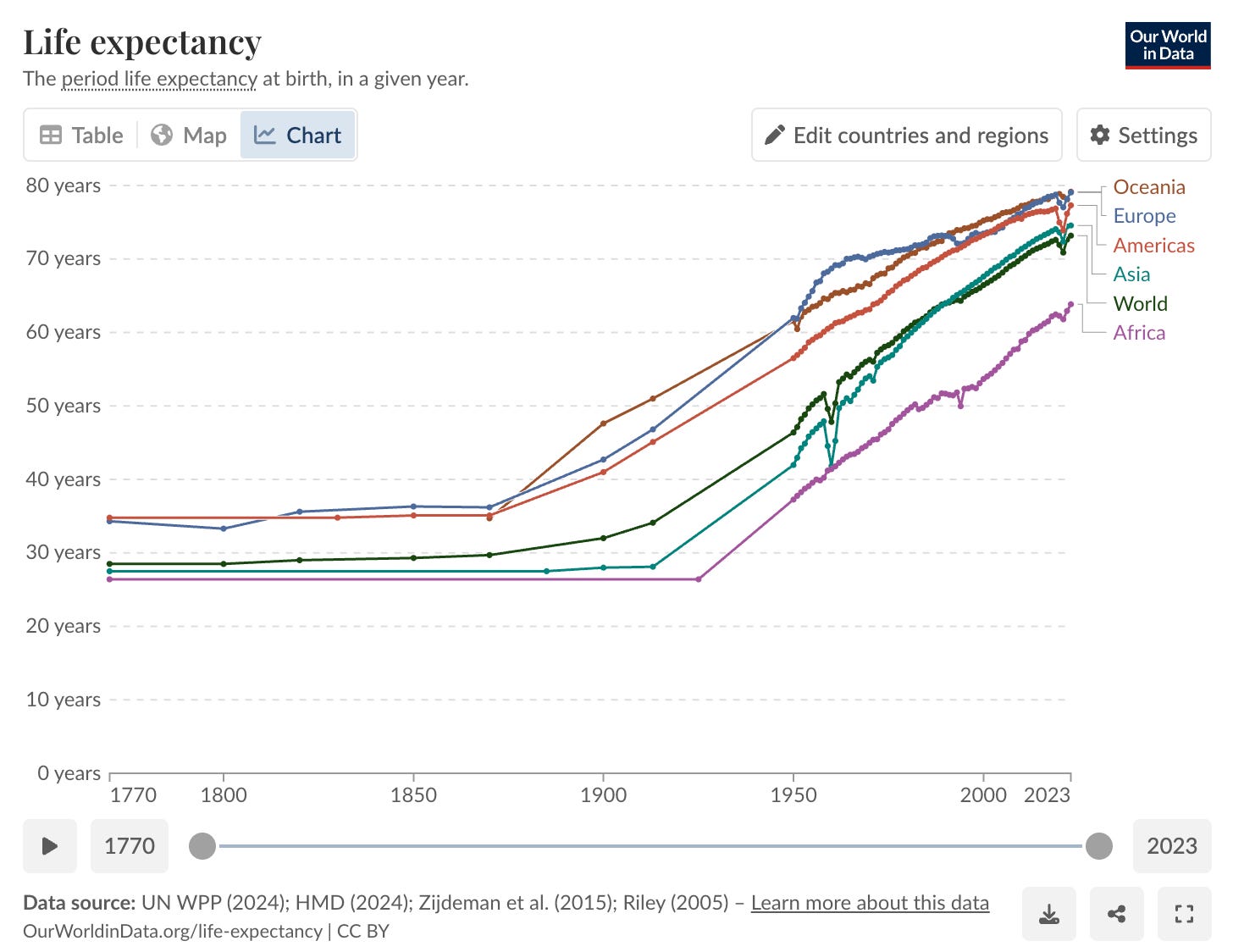

Humanity lifted itself out of extreme poverty somewhere between the 1800s and 1900s, extending the average life expectancy from 35 years to an average of 75 years old or higher.

How did we manage? Through technology and science.

The industrial revolution made it possible to build machines replacing human labor at scale, for the first time. As the cost of automation dropped below the cost of labor, automation replaced labor and jobs were slowly but surely replaced. At the same time, cheaper production costs significantly reduced the cost of goods and services, bringing down prices for everyone.

While many workers lost their jobs — in some cases leading to violent resistance by Luddites — more jobs were created over time. Why? Because there’s no such thing as a fixed amount of work; the economy isn’t a fixed pie.

Short explainer: Better known as the ‘lumb of labor-fallacy’, the term is commonly used to describe the false belief that increasing labour productivity, automation, immigration, or women’s participation in the workforce causes an increase in unemployment. The data show that just like the amount of labor is not fixed, neither is the size of the economy and as more work is done, the economy grows.

Historically, new jobs have emerged through scale: the middle manager is a recent invention; through improved living standards: as middle-class leisure time increased, it became fashionable to pursue activities that would have previously seemed frivolous or reserved for the rich; and lastly, by virtue of the technology itself: entire industries emerged after the invention of the automobile, the computer, and the Internet. Consider that arguably one of the most successful companies in humanity’s history, Google, is only 26 years old.

Aging populations and declining fertility rates

So we did it. We managed to create thriving populations of longer-living, healthier people. (The industrial revolution also unleashed destruction on an industrial scale, including two world wars, but that’s a topic for another discussion).

Two major trends that came of the back of that are an aging world population and slowing birth rates. Simply put, people get older and have fewer children.

It’s well-documented that slowing birth rates are inversely correlated with income. When women have control over if and when they want to have children (economic development and education is the best contraception in the world) and children have a lower chance of dying at a young age (according to UNICEF, 1 in 27 children died before reaching age five in 2023, compared to 1 in 11 in 1990) that tends to be a positive thing for society.

When we look into the future, we can see that an increasingly small number of young people will need to sustain an increasingly aging population. You don’t have to be an economist to understand that to do so would require a spectacular increase in productivity, unless we want to stagnate, or worse, fall back into poverty.

How are we supposed to do that? The answer is simple. We need automation, much more automation.

AI as normal technology

Now we have established that, let’s see if AI can deliver on its promise. The reality is that AI is going to take jobs away from people. Not 1/4 of their job. Not half of their job. All of it.

I know this to be true, because I’ve been responsible for it myself. For the past 6+ years, my job has been designing and building customer-facing AI assistants for enterprises. The most common use case: customer service.

A common misconception is that AI assistant needs to be on par with a human agents to be effective. However, the value of an AI assistant does not come from being excellent, it comes from being able talk to thousands of people at the same time. The chatbot for a large telecom provider I consulted for couldn’t answer every single query, but it would answer nearly half of them. While that may not sound impressive, what if I told you it was handling 1 million conversations every day?

It significantly reduced the number of FTEs across multiple customer service departments, ultimately resulting in job replacement.

I recognize this can be unsettling for people on an individual level — no one wants to feel replaceable — but doesn’t make it a bad thing per se. Realistically, job replacement is the result of a vicious circle of innovation and diffusion of technology in society, and, as authors and argue in their essay ‘AI as Normal Technology’, it’s not much different from the impact of the invention of electricity or the Internet:

Like other general-purpose technologies, the impact of AI is materialized not when methods and capabilities improve, but when those improvements are translated into applications and are diffused through productive sectors of the economy. There are speed limits at each stage.

They mention one important caveat though:

For sufficiently disruptive technologies, diffusion might require changes to the structure of firms and organizations, as well as to social norms and laws.

You see, during the early industrial revolution, capital owners benefited greatly from the newfound efficiencies of mechanized production, but the wealth they accumulated came largely at the expense of workers.

Labor laws and trade unions didn’t exist and despite working long hours, wages were barely enough to survive. Factories and mines would employ children as young as five or six; machines weren’t safe, so crushed limbs, severed fingers, and even death was common; and factories were filled with dust, smoke, and chemicals, contributing to chronic respiratory illnesses, and the deafening sound of machinery led to many workers suffering from hearing loss over time.

The real danger of too much automation too quickly isn’t that we’re all going to be without jobs, it’s that without government intervention the productivity gains flow primarily to capital owners, rather than being broadly distributed. Instead of wealth creation, you see wealth concentration.

The age of abundance

That said, when managed properly, AI could go on to transform the world for the better. This is important because, looking at the aforementioned trends, we need AI to succeed just in order to sustain ourselves.

If we beat expectations, and we might, it could usher in what people refer as ‘the age of abundance’: a utopian society where food, energy, housing, healthcare, and education can be produced and distributed at such low costs that they become effectively free or extremely affordable for all people. This idea usually goes hand-in-hand with the concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI), which would be an example of a government intervention for redistributing wealth.

Unfortunately, this is not the world we live in today. Healthcare isn’t free. Income inequality has risen, food insecurity is up, and global productivity is flat. For all the talk about AI and abundance, what we really suffer from is an abundance of scarcity.

When it comes to job security, a new WEF Future of Jobs Report predicts that by 2030, AI and automation “will create 170 million jobs while displacing 92 million roles as companies adapt to technological change”. In other words, more jobs will be created than replaced. It suggest AI is indeed ‘normal technology’ and follows the same cycle of innovation and diffusion as the technologies that came before it.

It means we have time. But not unlimited time. Collectively, we can either bend humanity towards an age of abundance or help a new aristocracy into power, in which the techbros become factory owners of tomorrow. If history teaches us but one single lesson it is this: the same things happen again and again, only differently.

Take care,

— Jurgen

About the author

Jurgen Gravestein is a product design lead and conversation designer at Conversation Design Institute. Together with his colleagues, he has trained more than 100+ conversational AI teams globally. He’s been teaching computers how to talk since 2018.

It's interesting to see the sentence "Humanity lifted itself out of extreme poverty" and no question on why did humanity end up in poverty in the first place? And what does poverty actually mean in that context? It's quite important to ask this because then the answer to "how did we manage?" cannot just be "science and technology" - we have to add social change and revolution to the equasion (not only Luddites!). All the science and technology would not have had an impact on humanity if all the resources had been reserved to the richest and most powerful individuals. I think it's crucial to keep that in mind while discussing AI because if the gains are not equally distributed, there will (and should) be another revolution. Especially given that even now, already now, the cost of AI affects some people more than others, and the gains remain in the hands of those who are currently winning the capitalist Monopoly

Deeply appreciate this in-depth perspective. Thank you.